Scientists show that the large North Pacific Garbage Island is made with plastics from all over the world

A group of researchers show that the North Pacific Garbage Island is constantly increasing and that it is made with plastics from around the world.

A study published in Environmental Research Letters reveals that centimeter-sized plastic fragments are increasing much faster than larger floating plastics on the North Pacific Garbage Island [NPGP], threatening the local ecosystem and potentially the global carbon cycle.

A recent study of the North Pacific Garbage Island

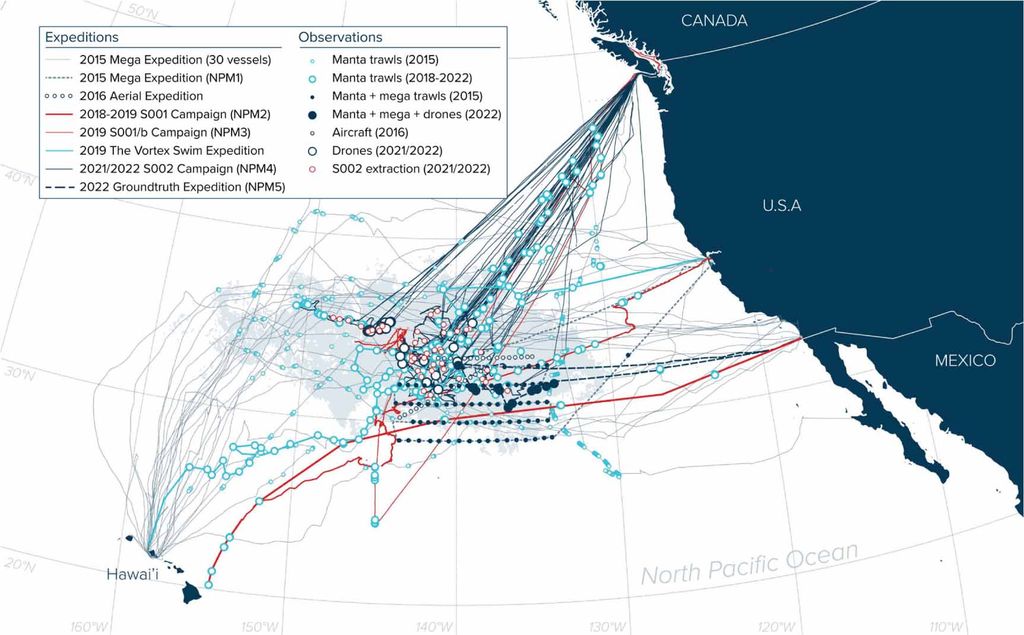

The research, which is based on the systematic studies of the NPGP carried out between 2015 and 2022 by the non-profit organization The Ocean Cleanup, found an unexpected increase in the massive concentration of plastic fragments that are probably new in the region and do not result from the degradation of objects already present.

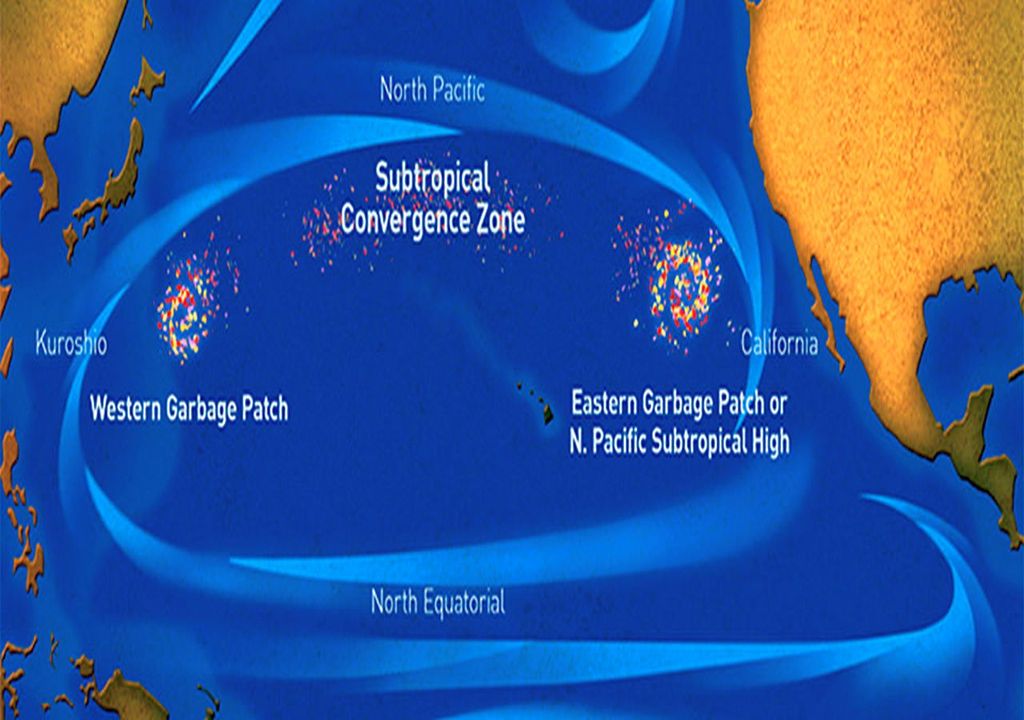

Researchers hypothesize that these fragments from the decomposition of decades-ago plastics discarded around the world are accumulating and increasing exponentially in this remote region of the Pacific Ocean.

The study examined 917 samples of manta trawls, 162 samples of mega drag nets, 74 aerial studies and 40 extractions from the cleaning system of 50 individual expeditions between 2015 and 2022.

Key findings include:

- Plastic fragments increased from 2.9 kg per km2 to 14.2 kg per km2 in seven years

- Between 74 and 96% of this increase may originate from foreign sources

- Small waste hotspots increased in concentration from 1 million per km2 in 2015 to more than 10 million per km2 in 2022

- Per km2, the average number of each size class of floating plastics has increased significantly: microplastics (0.5 mm–5 mm) increased from 960,000 to 1,500,000 items; mesoplastics (5 mm–50 mm) increased from 34,000 to 235,000 items; macroplastics (50 mm–500 mm) increased from 800 to 1,800 items per km2.

The volume of plastic waste in the region exceeds that of living organisms, threatening the ecosystem not only by the ingestion or entanglement of plastic by marine life, but also potentially impacting the global carbon cycle due to the grazing of zooplankton affected by the presence of floating microplastics.

Due to the increase in floating plastics, endemic marine animals are now in direct competition with new species that have colonized plastic waste and have moved to this remote part of the ocean.

Laurent Lebreton, lead author of the article, says: "The exponential increase in plastic fragments observed in our field studies is a direct consequence of decades of inadequate management of plastic waste, leading to the incessant accumulation of plastics in the marine environment.

"This pollution is damaging marine life and its effects we are just beginning to fully understand them. Our findings should serve as an urgent call to action for legislators involved in the negotiation of a global treaty to end plastic pollution. Now, more than ever, a decisive and unified global intervention is essential."

Researchers emphasize that, while countries are prioritizing the prevention of plastic pollution upstream, the interception and elimination of plastics already present in the global marine environment is essential to urgently mitigate the generation of increasingly small plastic fragments in the ocean for decades to come.

Reference

Laurent Lebreton et al, Seven years into the North Pacific Garbage Patch: legacy plastic fragments rising disproportionately faster than larger floating objects, Environmental Research Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ad78ed