Scientists are intrigued by the air in NASA's Mars sample tubes

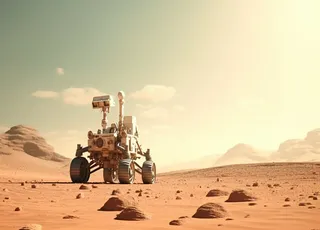

Scientists are excited about each rock core that NASA's Perseverance rover places in its titanium sample tubes, which are being collected for eventual delivery to Earth as part of the Mars Sample Return campaign.

Most of these samples consist of rock or regolite nuclei (broken rock and dust) that can reveal important information about the history of the planet and whether microbial life was present billions of years ago. But some scientists are equally enthusiastic about the prospect of studying the "headspace", that is, the air in the extra space around the rocky material, in the pipes.

"Mars air samples will tell us not only about the current climate and atmosphere, but also about their evolution over time," said Brandi Carrier, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

Scientists want to know more about the Martian atmosphere, which is composed mostly of carbon dioxide, but which may also include traces of other gases that may have existed since the formation of the planet.

With these samples we will be able to know more about the water vapor present on the red planet

Among the samples that could be brought to Earth is a tube filled only with gas deposited on the Martian surface as part of a sample deposit.

However, most of the gas from the rover's collection is in the space free of rock samples. These are unique, because the gas will be interacting with the rocky material inside the tubes for years before the samples can be opened and analyzed in laboratories on Earth.

What scientists collect from these samples will give an idea of the amount of water vapor that hovers near the Martian surface, a factor that determines the reason why ice forms where it forms on this planet and how the water cycle on Mars has evolved over time.

Scientists also want to better understand the smaller quantities of gases in the air of Mars. The most tempting thing, from a scientific point of view, would be the detection of noble gases, which are so little reactive that they may have been present, unchanged in the atmosphere, since their formation billions of years ago.

If captured, these gases can reveal whether Mars started with an atmosphere. (Ancient Mars had a much thicker atmosphere than the current one, but scientists are not sure if it was always present or if it developed later). There are also big questions about how the ancient atmosphere of the planet compared to that of the primitive Earth.