If a tropical storm does not form in the Atlantic soon, we would face an unprecedented event

It has been more than two weeks since Hurricane Ernesto formed, and as of today, the NHC does not forecast any new named storms within 7 days of peak hurricane season. This period would be the longest streak without the formation of a new named storm at the peak of hurricane season.

Experts are both awaiting and bewildered by what may happen in the 2024 hurricane season over the tropical North Atlantic, which was expected to be a hyperactive season, but is not as of yet.

Will 2024 hurricane season predictions be a huge flop?

According to expert Ed Piotrowski, @EdPiotrowski, the forecasts from several agencies for an extremely active hurricane season are in serious jeopardy. We are near the peak of hurricane season and we have not had a named storm in the Atlantic since Ernesto formed on 12 August.

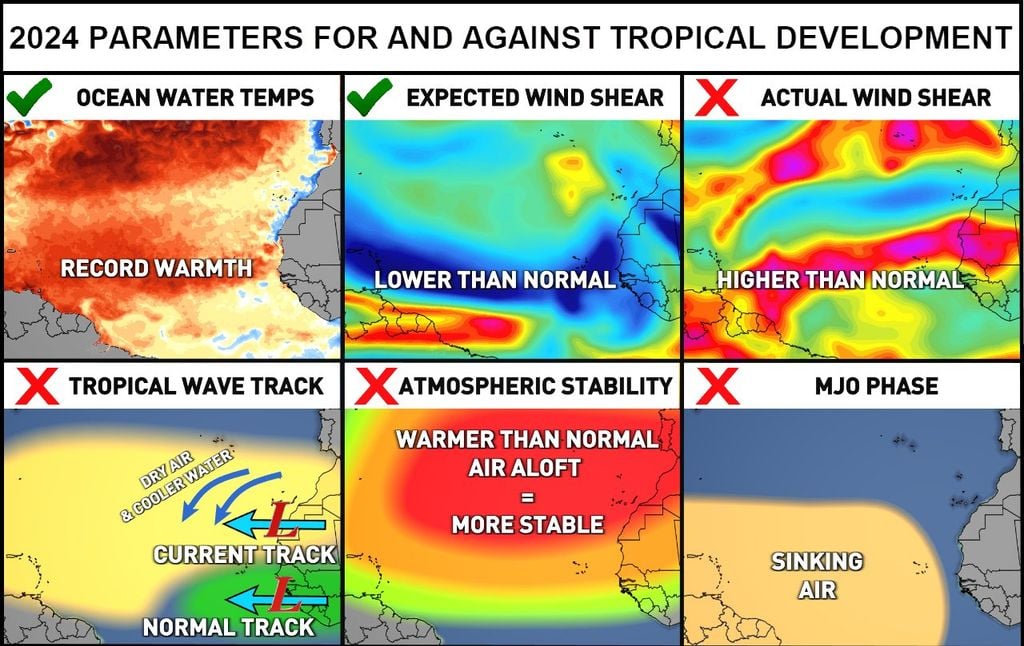

So what's going on? Why has it been so quiet, and what's in store for the rest of the season? The atmosphere is very complex, and there are multiple factors that meteorologists look at to determine how active a given hurricane season will be. Basically, they are these:

Surface water temperatures in the tropical Atlantic: currently very warm, favourable for developments

Water has been extremely warm in the main Atlantic development region, meaning there is plenty of fuel for tropical systems to gain strength. There are no signs of that changing in the coming months.

Wind shear: So far it has been high, inhibiting developments

As we enter the heart of a La Niña pattern, wind shear is typically lower than normal, favouring the development of tropical cyclones. For the past 3 weeks, in fact, it has been higher than normal. Wind shear can impede the formation of tropical systems. Those that do form have a difficult path. Wind shear disrupts the circulation of tropical systems, reducing their efficiency and causing them to weaken or even dissipate.

Trajectory of African tropical waves: far north, unfavourable

It is normal for tropical waves to advance from the African coast south of the Cape Verde Islands, where they take advantage of warm water and abundant atmospheric moisture.

Over the past 2-3 weeks, the very warm water setup over much of the Atlantic combined with relatively cooler water near the equator has pushed the tropical wave train northward. Tropical waves have been emerging from Africa over much cooler water and in a dust-laden atmosphere, all of which work against development.

With a more northerly track, these disturbances actually draw more dry air into the heart of the hurricane corridor, stifling thunderstorm activity. In addition, this more northerly track produces much higher than normal rainfall in the arid Sahara Desert.

Atmospheric stability: higher than normal, unfavourable for storm development

Normally, the atmosphere cools as you ascend. Since cooler air is denser and heavier than the relatively warmer air near the ground, it naturally tends to rise. This year, the air aloft has been warmer than usual, leading to increased stability that suppresses thunderstorm activity.

We're not 100% sure why this is happening. It could be a result of climate change or even related to the 2022 eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'Apai volcano, which injected 150 million metric tons of water vapour into the stratosphere. The more water vapour there is aloft, the more heat it absorbs.

Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO): current negative or inhibitory phase of storms

The MJO is an atmospheric wave that occurs in the tropics and travels around the world over a period of 30 to 60 days. This global wave includes phases of intensified and suppressed or inhibitory precipitation. In the intensified phase, air is more likely to rise and produce thunderstorms, while in the suppressed phase, thunderstorms have difficulty forming due to sinking air. Much of the Atlantic is currently in a storm-inhibiting phase. With these elements, the Atlantic Ocean should come alive in the coming weeks, but this remains to be seen.

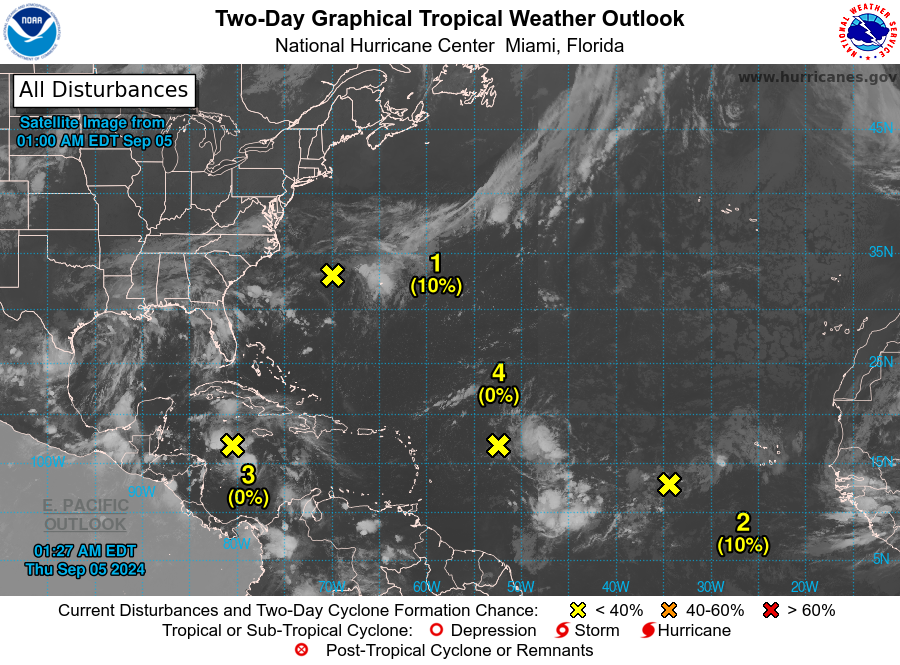

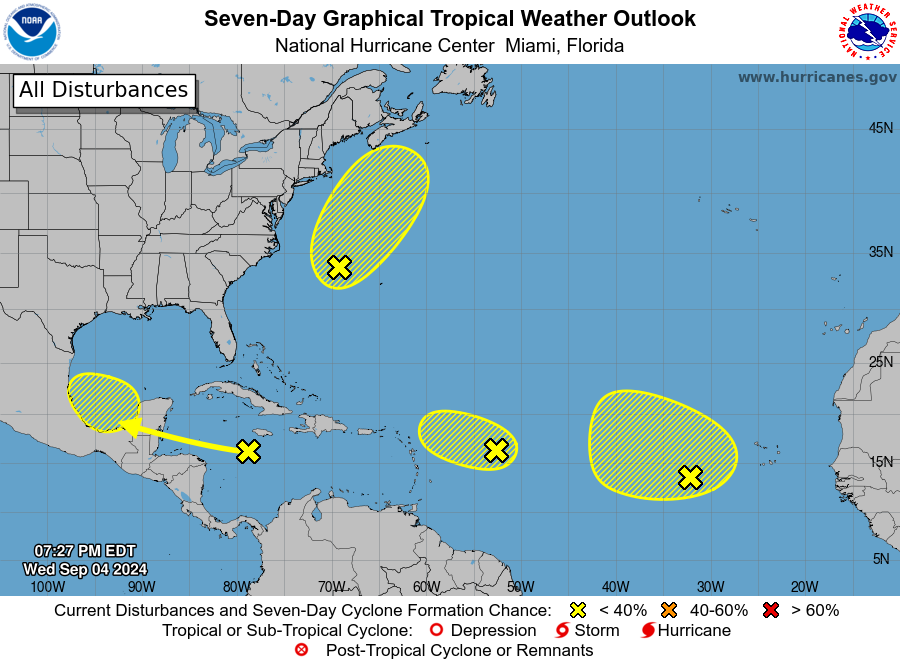

Four areas are monitored by the NHC in the tropical Atlantic

There are very low chances for tropical development in four areas, according to the National Hurricane Center. None of them has a medium chance of becoming a depression or tropical storm within 7 days. Tropical development is centred in four areas: one in the Caribbean, one off the East Coast and a pair of systems in the central and eastern Atlantic.

Only the areas and probabilities of becoming a named tropical cyclone are indicated:

Northwest Atlantic

- Formation chance through 48 hours...low...10 percent.

- Formation chance through 7 days...low...20 percent.

Eastern Tropical Atlantic

- Formation chance through 48 hours...low...10 percent.

- Formation chance through 7 days...low...20 percent.

Northwestern Caribbean Sea and Southwestern Gulf of Mexico

- Formation chance through 48 hours...low...near 0 percent.

- Formation chance through 7 days...low...30 percent.

Central Tropical Atlantic

- Formation chance through 48 hours...low...near 0 percent.

- Formation chance through 7 days...low...10 percent.

It's been over two weeks since a named storm (Hurricane Ernesto) developed in the Atlantic basin. The next Atlantic storm will be named Francine. Remember that September is the busiest month of the Atlantic hurricane season, but as of now there is no tropical storm within 7 days and that is very rare. There is still a long way to go in this hurricane season.