Modern planes emit less carbon dioxide, but their condensation trails warm the planet more

The move toward more efficient aircraft could have an unexpected effect: longer-lasting condensation trails that, by trapping more heat, could aggravate global warming, according to a new study.

The aeronautical industry has evolved to make aircraft that fly higher and faster and faster. Thus, it seeks - and gets - more efficient flights, which leave an increasingly less significant carbon footprint.

However, this improvement in efficiency could have an unsuspected side effect. According to a recent study by Imperial College London, the condensation trails of the most modern aircraft tend to stay longer in the atmosphere, and therefore retain more heat, which could contribute significantly to global warming.

Every day, thousands of planes travel the planet at high altitudes. The most modern ones are designed to fly above 12 km in height, where they can take advantage of atmospheric conditions to have lower aerodynamic resistance and reduce fuel consumption.

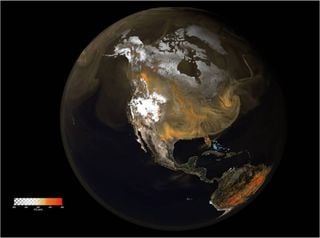

Condensation trails are clouds of ice, in the form of long lines, which sometimes arise at the passage of an airplane, by condensation of the water vapor contained in the emissions of the engines, as defined by the Spanish Meteorological Agency.

Water vapor is a greenhouse gas, since it favors the retention of heat in the atmosphere. Therefore, the condensation trails, being water vapor, also retain heat.

Although scientists cannot specify the exact impact of the stelas on global warming, they suspect that it could be more important than the one caused by aviation emissions.

"The clouds produced by aircraft - known as condensation trails - contribute to more than half of the positive radiative forcing of aviation, but the magnitude of this warming effect is very uncertain," the work says.

Unexpected effect of the increased efficiency of aviation

Through machine learning, the researchers analyzed the satellite data of more than 64,000 condensation stelae of different types of aircraft on their flights over the North Atlantic. They compared the satellite observations with the air traffic data of the Federal Aviation Administration.

Scientists used infrared bands to detect the steles, with a resolution of 2 km. In addition, they used reanalysis data on wind, humidity and temperature, to characterize the conditions in which the steles were formed and how they evolved.

The analysis of these data revealed that the newer aircraft, such as the Airbus A350 and the Boeing 787, which fly above 12,000 meters in height, emit less CO2, but their condensation trails last longer in the atmosphere.

The lead author of the study, Dr. Edward Gryspeerdt, said: "the unwanted consequence of this is that these planes are now creating more condensation trails, of longer duration, trapping additional heat in the atmosphere and increasing the climate impact of aviation."

The study also suggests that, by further improving the engines and the amount of gases they emit in combustion, the life of the steles could be shortened.

"This does not mean that the most efficient aircraft are a bad thing, far from it, since they have less carbon emissions per passenger-mile. However, our finding reflects the challenges facing the aviation industry to reduce its climate impact," Gryspeerdt added.

Previous research based on modeling had proposed this hypothesis, but this is the first work that confirms it based on observations of real aviation. The study was published this week in Environmental Research Letters and had the support of several institutions, including NASA.

Reference of the news:

Gryspeerdt, E. et al. “Operational differences lead to longer lifetimes of satellite detectable contrails from more fuel efficient aircraft”. Environmental Research Letters Published on August 7, 2024.