Krill poo reveals importance of tiny crustacean in carbon storage

Antarctic krill poo shows the crustacean plays an important role in carbon storage, harbouring as much as mangroves and seagrass, and should be protected.

A single species of small marine crustaceans are as valuable as key coastal habitats say researchers from Imperial College London.

Antarctic krill can store similar amounts of carbon to key ‘blue carbon’ coastal marine habitats, like mangroves, saltmarshes and seagrasses, but are subject to the same effects of global heating and potential overfishing, and so should be similarly protected.

Power of krill poo

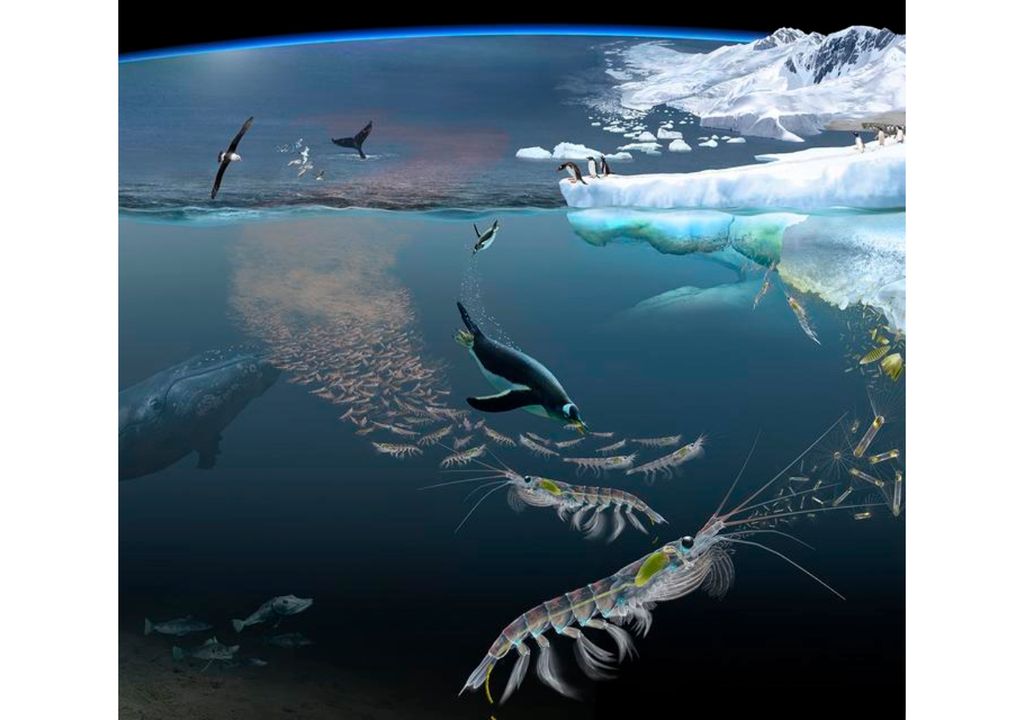

Krill are small – and abundant – crustaceans that reside in the Antarctic seas. They’re consumed by larger animals in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, like whales, seals and penguins, but they’re also fished for food and fishing bait and have uses in aquaculture and as dietary supplements.

Krill eat microscopic plants called phytoplankton, which remove carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis. When krill moult their exoskeletons or defecate, the carbon they’ve absorbed sinks into the deep sea where it remains for a very long time.

“For the past decade we have been piecing together the role krill have in carbon cycling, finally resulting in this amazing finding that krill, and their poo, store similar amounts of carbon as some coastal marine plants,” explains Dr Emma Cavan, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial.

Antarctic krill lock at least 20 million tonnes of carbon into the deep ocean annually, the study found.

“Antarctic krill are well known for being at the centre of the unique Southern Ocean ecosystem and supporting an important fishery. But this study paints another picture of krill – on their key role in storing carbon,” says Professor Angus Atkinson, from Plymouth Marine Laboratory.

A rain of krill poo

Krill’s large numbers are key to their carbon storing performance; they can form swarms of up to 30 trillion individuals, that produce showers of large, fast-sinking faecal pellets and other waste products.

“One of the amazing things about krill is that they form massive swarms, which can be over a kilometre in length,” says Dr Anna Belcher, from the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. “This drives a huge 'rain' of krill poo after feeding, making krill globally important for locking carbon away from the atmosphere. So, let's make sure we look after these amazing crustaceans!”

These waste products are typically stored away for at least 100 years the study revealed, but were surprisingly shallow, at an average depth of just 381m, further enhancing their potential. Together, these factors make the carbon storage from krill similar to that from coastal blue carbon plant stores.

Protect to preserve

Rapid polar climate change and expanding fishing are impacting Antarctic krill, and the researchers say both krill populations and their habitat need protection to preserve this valuable carbon sink.

“This study shows how we as people are connected to a small creature in a remote location,” says Dr Simeon Hill, from the British Antarctic Survey. “We benefit from its actions in removing carbon but we also affect it through our own actions which drive climate change.”

Valuing this ecosystem in terms of carbon storage emphasises how crucial it is to meet climate goals and work towards including carbon in conservation policies.

“I hope this means we can now work towards conserving krill and their valuable Southern Ocean ecosystem with the same gumption as we are seagrasses and mangroves,” Cavan concludes.

News reference

Cavan, E. L, et al (2024) Valuing carbon sequestration by Antarctic krill faecal pellets, Nature Communications.