Does lightning strike on Venus? Astronomers put an end to long-running debate

The occurrence of lightning on Venus has been debated for decades, with multiple spacecraft failing to detect it. Do we now have a definitive answer?

Researchers at the University of Boulder Colorado may have put an end to a surprisingly long-running debate in space science — does the choking, tumultuous atmosphere of Venus see lightning strikes?

As detailed in the findings, published in Geophysical Research Letters, the researchers found strong evidence that no, it probably doesn't. Or, at least, not very often.

"There’s been debate about lightning on Venus for close to 40 years,” said Harriet George, lead author of the study and researcher at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP). “Hopefully, with our newly available data, we can help to reconcile that debate.”

A world of extremes

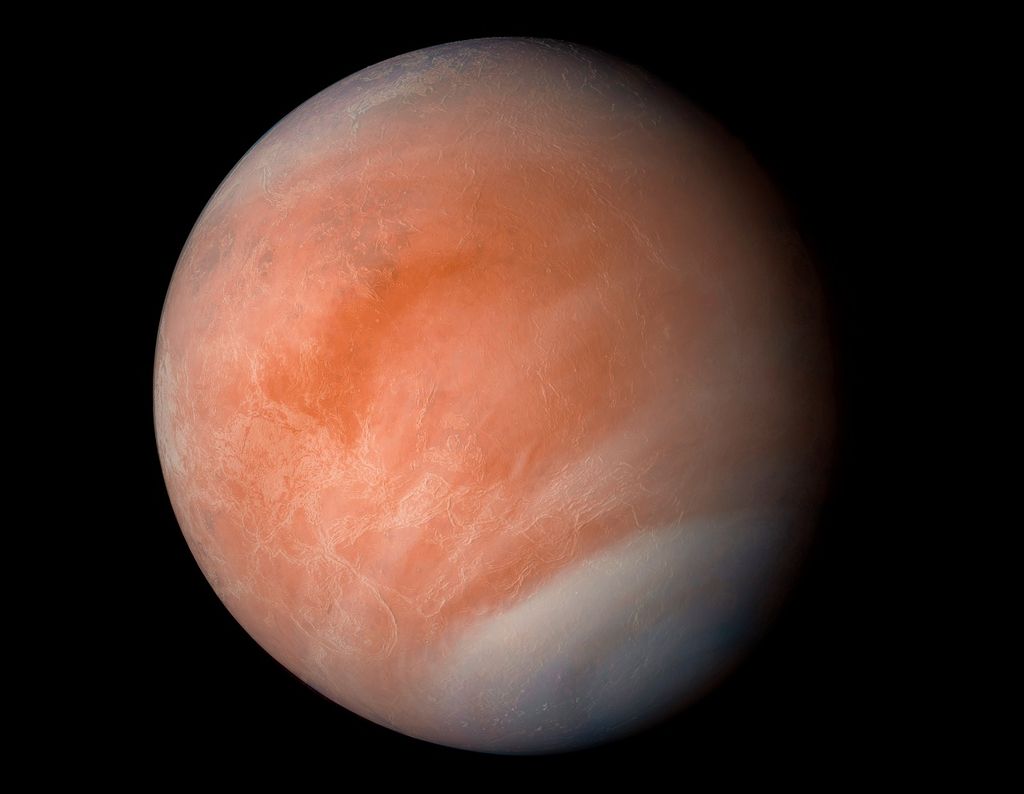

Similar in size to the Earth, Venus is about as hospitable as a rugby player's armpit and several times as noxious. Its carbon-dioxide-rich atmosphere suffocates the planet, turbo-charging temperatures to more than 480°C, while the crushing pressure on the surface is equivalent to being 1km below Earth's oceans.

To explore this world of extremes, the authors turned to a scientific tool that wasn't designed to study Venus at all: NASA's Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018 to gather data from the Sun.

On its journey towards our star, the probe made a pass of Venus in February 2021, picking up dozens of so-called 'whistler waves' in the atmosphere. These are pulses of energy which, on Earth, are triggered by lightning bolts and named after the associated whistling sounds picked up by early radio operators using headphones.

Whistler waves were first identified in Venus' atmosphere back in 1978, when NASA's Pioneer Venus spacecraft entered the planet's orbit. For many scientists, this was evidence of probable lightning strikes, but others disagreed, arguing that the whistler waves could be caused by something else.

Whistler waves, but not as we know them

When the authors of the present study analysed the whistler waves identified by the Parker Solar Probe, they noticed something surprising — the waves were travelling in the wrong direction. Instead of moving out into space, as is expected during thunderstorms, these waves were moving down towards the planet.

As the authors explain, it's not entirely clear what's causing them to do this. They suspect it may be something to do with a phenomenon known as magnetic reconnection, where the magnetic field lines that surround Venus come apart then snap back together, with explosive results.

The researchers say they still need to analyse more whistler waves to completely rule out lightning as a cause, but they will have a chance to do this in November 2024, when the Parker Solar Probe makes its final pass of Venus. This fly-by will be closer than the last, with the spacecraft set to skim the upper layers of Venus' atmosphere, at a height of 250 miles above the planet's surface.